As per an analysis conducted by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), cases against MPs elected to the 15th Lok Sabha in 2009 were pending for an average of seven years. Also, 24 MPs were re-elected even after they had declared criminal cases during the 2004 Lok Sabha elections as well. The problem is made more complex by the fact that the delay in trial often leads to a low rate of conviction of MPs and MLAs. Low conviction rates and insufficient deterrents allow political parties to continue fielding candidates with pending criminal cases. The cycle is completed by the tragedy of voters, who keep re-electing such candidates due to lack of options. Further, as a result of a low number of convictions, the provision in the Representation of the People Act, meant to provide a safeguard against convicted candidates acting as representatives, does not seem to serve its full purpose.

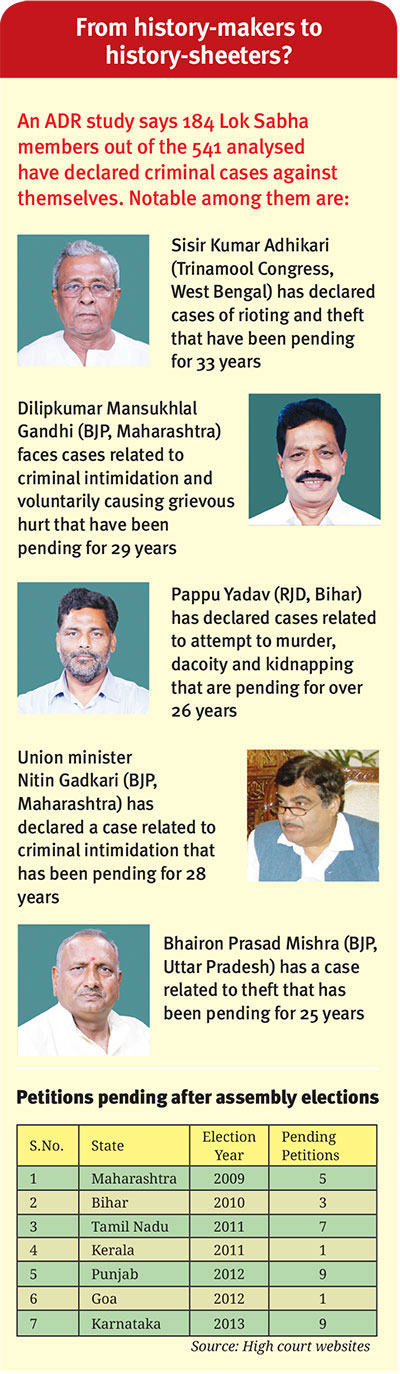

The ADR’s study of criminal cases declared by newly elected MPs of the 16th Lok Sabha reveals the extent of the rot. As many as 184 Lok Sabha members out of the 541 analysed have declared criminal cases against themselves with the average pendency of criminal cases declared by MPs being seven years. As many as 69 sitting MPs have 171 criminal cases that have been pending for 10 years or more, with 45 of them having a total of 85 serious cases pending for over a decade.

MPs with criminal cases have their own ‘high achievers’. Sisir Kumar Adhikari of the Trinamool Congress from West Bengal has declared cases of rioting and theft pending for 33 years. Not to be left behind, there are Dilipkumar Mansukhlal Gandhi of BJP from Maharashtra with cases related to criminal intimidation and voluntarily causing grievous hurt that have been pending for 29 years; Pappu Yadav of the RJD from Bihar who has declared cases related to attempt to murder, dacoity and kidnapping pending for over 26 years, BJP leader Nitin Gadkari who has declared a case related to criminal intimidation that has been pending for 28 years and Bhairon Prasad Mishra of BJP from Uttar Pradesh with a case related to theft, pending for 25 years.

When it comes to heinous crimes, five Lok Sabha MPs have declared a total of five cases of murder, seven have declared a total of 12 cases of attempt to murder, four have declared 12 cases related to kidnapping and six have declared 13 cases of robbery and dacoity which have all been pending for over 10 years.

The delay in administering justice by courts is prevalent even in matters related to election petitions, many of which remain unsettled even after the terms of the elected representative have ended. This is despite Section 86(6) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 prescribing that the court in matters relating to election petitions (as far as possible) hold trials on a “day-to-day” basis. Also, Section 86(7) declares that every election petition will be tried as expeditiously as possible and all efforts will be made to conclude the trial within six months from the date on which the petition was filed.

An analysis of election petitions filed after various assembly elections reveals that a large number of election petitions remain pending in various high courts across the country. (See table for a list of a few states where petitions filed after the respective assembly elections remain pending.)

The situation seems grim, especially in cases of states like Maharashtra, Bihar, Tamil Nadu and Punjab, where a large number of petitions are likely to be declared infructuous, if they remain pending in courts after the term of the current assembly expires. Considering that the assembly terms for most of these states are more than half over, the whole point of the exercise is defeated, if the election of the winner concerned is eventually set aside by the court.

The issue of expediting trials against sitting MPs and MLAs had assumed significance even before the supreme court judgment in March 2014, directing all trial courts to expedite and conclude criminal cases against MPs and MLAs within one year from the date of framing of charges, when the 244th law commission report strongly felt that charges framed against sitting MPs and MLAs be concluded speedily, on a day-to-day basis, within one year. The political class argues that most such cases are politically motivated, with an intention to disqualify an honest candidate, framed prior to elections. In response to such arguments, the law commission recommended that elected representatives be disqualified if they have charges framed against them for more than one year and less than six years before an election in relation to offences which carry punishment of jail for a period of five years or more. The problem raises a complex question. Why would legislators initiate or allow reform that would in effect bar their own participation in active politics?

Prime minister Narendra Modi’s speech in the Rajya Sabha, in which he emphasised the urgent need to cleanse parliament of members with tainted records through the judicial mechanism within one year, brought with it much reason for hope. However, in response to Modi’s suggestion for fast-tracking cases against elected representatives, the supreme court on August 1 said fast-tracking only a certain category of cases was not desirable since such “piecemeal” steps would only lead to a delay in deciding other cases. The court instead asked the government to work out a comprehensive policy which would fast-track the entire criminal justice system in the country, without creating special courts for any one category of cases.

What is primarily missing today is the lack of will in the political class to be the change the public expects. Instead of waiting for the judiciary to prove guilt in a trial, parties must themselves take up the responsibility of denying tickets to ‘history sheeters’ and candidates who have declared serious criminal cases against themselves. It remains to be seen how the plan to speed the country’s criminal justice system will take shape considering that over one-third of the current Lok Sabha consists of crime-tainted members. For now, we can only hope that our legal system is able to evolve in order to combat the threat of increasing criminalisation of politics.

(Baldawa is a researcher with the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR).)